Katie Hughes, a Museum Studies student at the University of Aberdeen, joined the National & International Partnerships Department on a work placement in June 2017. Here she writes about a mixed media sculpture, Fiosaiche (Soothsayer), 2016, by Will MacLean, acquired by University of Aberdeen Museums in 2017 with an NFA grant of £900.

This mixed media sculpture consists of a hand-held church collection box bearing a temporary object movement label from University of Aberdeen Museums. Within the box is a copy of a prayer book and key from the University’s collection which belonged to a fiosaiche, a soothsayer or fortune teller, who lived on the Isle of Lewis during the mid-19th century. The artwork was inspired by the deeds of the fiosaiche and his ultimate downfall.

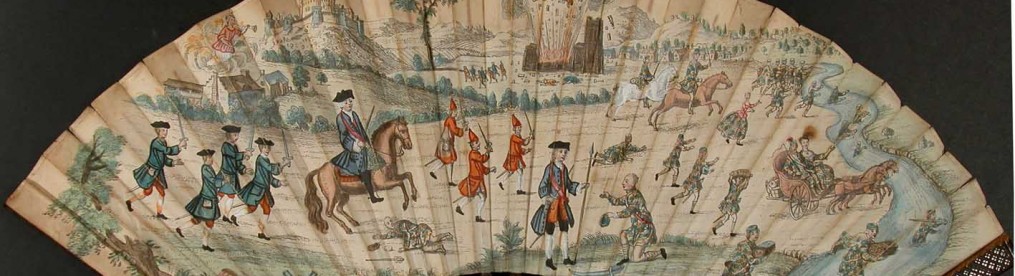

Mixed media sculpture, Fiosaiche, 2016, by Will MacLean

In 1899, the Reverend Malcolm MacPhail, Minister of Kilmartin, wrote about the fiosaiche of the Isle of Lewis. He claims that the fiosaiche was a divisive figure whose activities caused trouble between neighbours.

There was a Fiosaiche – soothsayer – who pretended to be able to foretell future events, and to detect criminals in districts far and near. By so doing he often caused a good deal of ill-feeling and dispeace. At the period of which we write – in the forties – the individual who had consulted him and the neighbours incriminated, were from Gearraidh na h-Aibhne, a district thirty-five miles from Ness.

John Munro Mackenzie, Esq, Factor of the Lewis Estates, accompanied the parties concerned to the Fiosaiche’s house. Mr MacKenzie interviewed him, and sharply reproved him for his dispeacable conduct, in setting good neighbours at each other’s throats with his lies. The Fiosaiche boldly replied that he told no lies, and that he had said nothing but what he ascertained from the Book. Mr MacKenzie said to him, “Can you read? What book do you consult?” He replied, ‘Though I cannot read, I can understand the signs. The book is my property, and you have no right to ask me questions about it.’

Rev MacPhail’s account is particularly valuable because he describes the method by which the soothsayer claimed to foretell the future and solve the problems which were brought to him.

… Mr Mackenzie asked his Ground Officer to go in to the Fiosaiche’s house and to bring out the book with him. To Mr MacKenzie’s surprise the book was none other than the Bible. An old rusty key, and a number of ribbons of various colours were attached to the Bible. By applying this key to certain of the ribbons, he maintained that by observing certain signs he was able to solve the different problems that came before him.

Mixed media sculpture, Fiosaiche, 2016, by Will MacLean

During this period Pagan activity and witchcraft were ruthlessly suppressed by the established Church and Rev MacPhail went on to recount how the Bible was confiscated and that without it the fiosaiche lost his power.

Mr MacKenzie took possession of the Bible, and carried it away in spite of the false prophet’s protestations and loud curses. He thus crippled, maimed and discredited the Fiosaiche for the rest of his life.

(Extracts from Rev Malcolm MacPhail, Minister of Kilmartin, 1899)

The fiosaiche’s Bible and key were later presented to the University of Aberdeen by Alexander Thomson of Banchory House who received them from a Minister in Langholm in 1863. In his accompanying letter the Minister wrote:

I said you should have it for your museum, so now I send it as a contribution to the history of superstition in the 19th century…

(Extract from letter to Alexander Thomson from Rev Mr F C Watson of Langholm, 1863)

I find this piece of artwork both fascinating and layered with history. I was drawn first to the story associated with the work, and continued to be drawn in by it; particularly the fact that it was inspired by objects from the museum’s collection; and that the original objects of inspiration have a traceable origin and accompanying letters detailing their history.

K Hughes

MLitt Museum Studies

University of Aberdeen